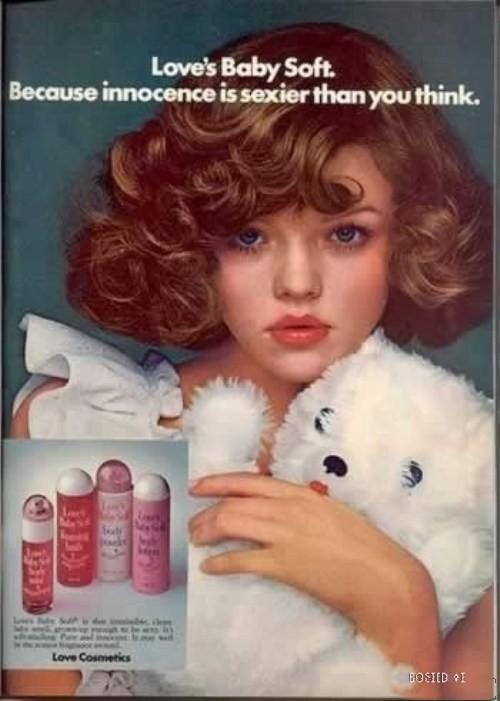

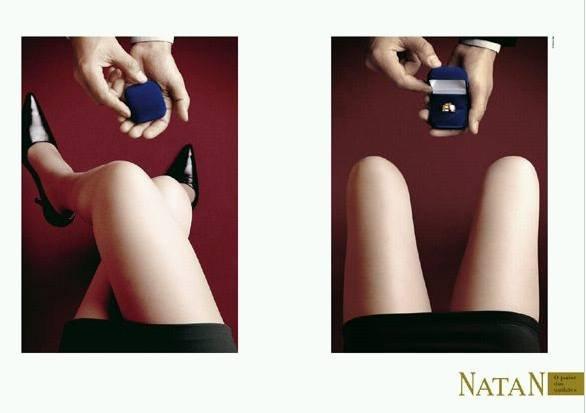

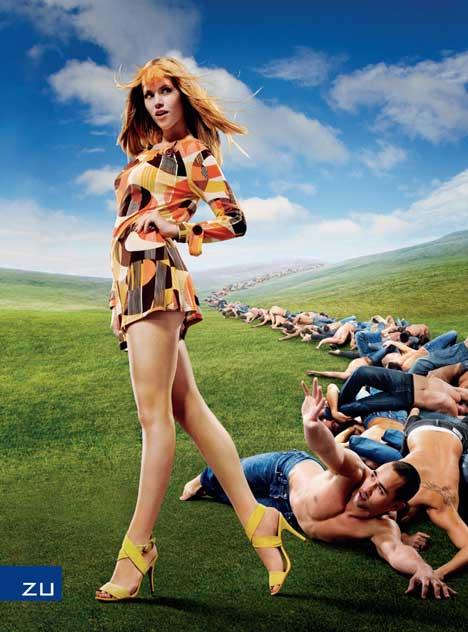

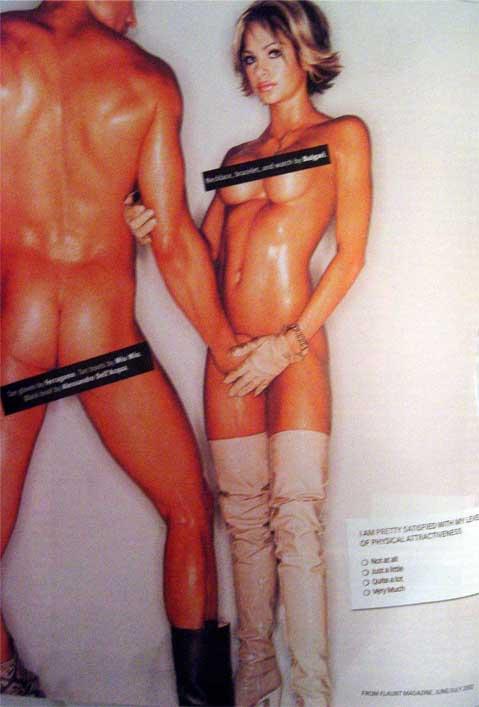

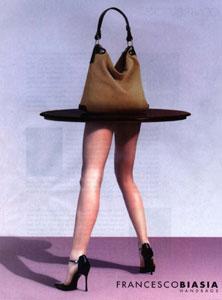

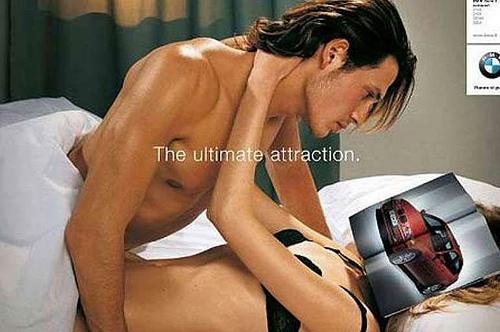

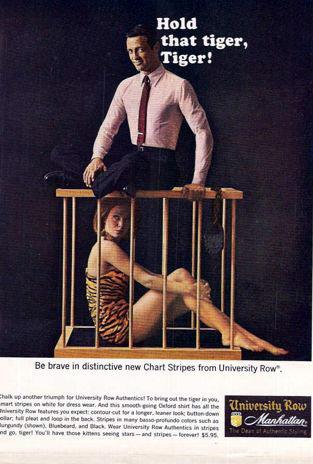

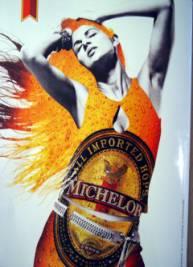

You may not even notice the images, they are that frequent. Every day you see hundreds if not thousands of advertisements, attempting to sell you the latest product, car, or fancy gadget. These images are so pervasive in today’s society that many times we glance at them and barely even notice. Watching television only adds to our viewing of advertisements that we probably don’t think we are paying much attention to, but whose messages knowingly or not, seep into our brains. And sometimes, that’s exactly the problem, people are so used to what the media puts forth, that no one ever stops to question what is being shown, and how images are portrayed. One of the most pervasive problems in advertising that has become part of mainstream culture is the objectification of women. The images of women through television, magazine, billboard, and other advertisements have become increasingly sexual in nature, as well as more and more degrading to women. The images that are viewed every day do affect those that view them, however, and in more serious ways than those creating the advertisements seem to realize.

Before delving into their research in a study, “Women as Sex Objects and Victims in Print Advertisements” published and performed by Julie M. Stankiewicz & Francine Rosselli, information about rape and sexual assault is presented as a consequence of the sexual images shown throughout the media. The article brings up prior findings that 20 to 25% of women while in college will be victims of rape or attempted rape. Not only is this number exceptionally high, but the percentage of college aged men who report likelihood of raping a woman if they knew there was no way that they could be caught sits right around 35%. The article presents prior research which shows that “the simultaneous presentation of women as sex objects and victims in various forms of media increases acceptance of violence against women” (580). The article states that the explicit content and victimization that was at one time only linked to pornography has slowly seeped into the world of advertising. Even with its vast amount of background research, the main aim of this study was to examine to what degree women were portrayed as victims in advertisements, as sex objects in advertisements, and as both sex objects and victims. A more minor objective was to observe the extent to which women were depicted as aggressors, and whether they were sexualized or not sexualized. Thirdly, it was viewed whether the presentation of all the previous components varied from magazine to magazine. It was hypothesized that in half of all advertisements that women appeared in, they would be depicted as sex objects.

4,136 advertisements from 58 magazines were viewed in this study, which included men’s, women’s, entertainment, news and business, special interest, and teen magazines. They were selected by popularity and large amount of magazine circulation. The criteria for deciding whether women were sex objects were very basic, and only required that her sexuality was being used to sell a product. The researchers left this fairly open ended so that participants could use their own judgment of deciding this. For victimization, however, there was a much stricter set of criteria that had to be met, including: men dominating women, an explicit depiction of violence being committed against a woman, a woman in bondage, etc. A woman would fall into the category of aggressor if she was presented as committing an act of violence or preparing to commit a violent act. In line with the predictions of the study, 51.80% of advertisements that were viewed in this study revealed women as sex objects, and sat at 75.98% for advertisements that were pulled from men’s magazines. The only category of magazine that had a higher percentage of ads with women as sex objects was adolescent girls’ magazines. When women were portrayed as victims it was a much smaller percentage in this study, sitting at an average of 9.51%, but with women’s fashion magazines having a higher statistic of 16.75%. About 73% of the time when women were portrayed as victims, they were also portrayed as sex objects. This o “simultaneous presentation of women as sexualized and distressed reinforces the association between women’s sexuality and the experience of physical and emotional pain. Therefore, such images may function to normalize violence against women” (585). Women were portrayed as aggressors a very small percentage of the time, but when they were presented as aggressors 75% of the time they were also presented as sex objects and were almost never portrayed simultaneously as aggressors and not as sex objects.

A study, “Exposure to Sexually Objectifying Media and Body Self-Perceptions among College Women: An Examination of the Selective Exposure Hypothesis and the Role of Moderating Variables” by Jennifer Stevens Aubrey explored a concept called objectification theory. This theory argues that the media places looks and physical appearance of women at such a high standard that it causes them to self-objectify or to feel apprehensive or embarrassed about their bodies. At the same time, they pose, that it is also possible that self-perceptions of the body affect whether women will select or avoid sexually objectifying media. The main goal of this study “was to investigate the directionality of the relations between exposure to sexually objectifying media and both self-objectification and negative affect about the body” (160). The study researched sexual objectification in the media and found that according to previous research stated that magazine photographs vastly focused on women’s bodies, or body parts, at times cutting out their heads and faces altogether. They also state that among sexual themes in television, the second most common is that of women being judged by their personal appearance. Aubrey writes that it would make sense that if women are habitually exposed to the appearance of women in this state, and the amount of sexual objectification female bodies in the media endure, that women become socialized to think of and treat their own bodies as objects. The study’s findings were that, overall, subjection to sexually objectified images did bring down women’s view of their bodies, but had the greatest influence on a specific sub-group: women who were low in global self-esteem. It has been found that it is usually college aged women who are most commonly found to be low in global self-esteem. One group the study also touches on is young adolescent women, of who commonly view fashion magazines. This age is significantly more susceptible to the images in magazines, because they are considered to be at a vulnerable time in their lives.

Another study, “A Picture is Worth Twenty Words (about the Self): Testing the Priming Influence of Visual Sexual Objectification on Women's Self-Objectification” continues to explore the depth of the objectification theory. They state that women who self-objectify not only have greater risks for negative opinions about their body but are more at risk for mental health problems and eating disorders. Self-objectifying is an issue because it focuses on physical rather than mental attributes. This is done mainly, they say, because of the increase in sexual objectification of women and their bodies in the media. This study poses the idea that many previous studies “do not address whether short-term exposure to media stimuli could also activate a temporary state of” (2). This study also believes that other studies do not say what it is specifically that makes women feel badly about their bodies.

Two studies were conducted to help dig deeper into the theory of self-objectification. Study One gave college aged women were given a definition of sexual objectification and then asked to rank how sexually objectifying those images were based on that definition. This study’s results insinuated that pictures of women showing more skin were perceived to be more sexually objectifying. Study Two was designed to measure the effects that the images from Study One had on the same women and their levels of self-objectification. The main part of the study had participants view pictures from magazines and they were then asked to write a brief statement about what the article that image came from was probably about. There were 12 photos total that each woman potentially saw six of, six of which were experimental and six that filled spaces (these photos came from home décor magazines or were photos of landscapes, etc.). On average there were just over two statements of response that regarded appearance. It was also concluded that women who at the beginning of the study reported high in consciousness of body and who were exposed to the set of experimental, body displaying, photos reported more self-objectification.

Not only does the media affect how women portray themselves, but it also seems that it skews how intimate partners, especially male in regards to female, view their partner. A study, “Self- and Partner-objectification in Romantic Relationships: Associations with Media Consumption and Relationship Satisfaction” tested whether viewing mass media had effect on self-objectification and objectification of one’s partner. Undergraduate males and females completed self-report measuring self-objectification, the objectification of their romantic partner, relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and exposure to objectifying media. Overall, men reported higher levels of objectification of their partner, and very little difference between the sexes existed for self-objectification. This shows how the media can not only affect the relationship one has with themselves and their body, but with a romantic partner, as well.

In conclusion, all these studies help to reinforce the point that not only is it obvious that advertisements use sexual objectification of women’s bodies, but that it is increasingly harmful to their well being.

Works Cited

Aubrey, Jennifer Stevens. "Exposure to Sexually Objectifying Media and Body Self-Perceptions among College Women: An Examination of the Selective Exposure Hypothesis and the Role of Moderating Variables." Sex Roles 55.3-4 (2006): 159-72. Web.

Stankiewicz, Julie M., and Francine Rosselli. "Women as Sex Objects and Victims in Print Advertisements." Sex Roles 58.7-8 (2008): 579-89. Web.

Zubriggen, Eileen, Laura Ramsey, and Beth Jaworski. "Self- and Partner-objectification in Romantic Relationships: Associations with Media Consumption and Relationship Satisfaction." Sex Roles 64.7-8 (2011): 449-62. Web.